Traditionally in the UK it was used to create fodder for livestock or for timber and was cut higher up the stem, rather than at ground level (known as coppicing) to protect the regrowth from grazing animals.

It is an extremely effective way of managing certain species such as willow or lime trees, however not all trees (most conifers, birch and cherry for example) will respond well to pollarding.

The age of the tree to be pollarded is also critical as younger trees respond much better to this type of management whereas veteran trees almost certainly wouldn’t be able to cope.

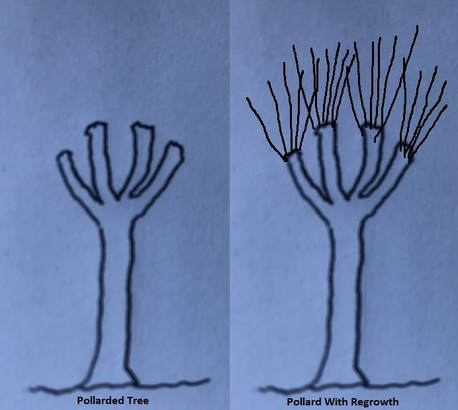

The initial process will encourage rapid responsive growth, usually emerging from an area near the pollard point (end of the cut stem or branch) but could grow from anywhere on the stem or branch.

The above diagram will not win any prizes for its artistic merit, but it hopefully shows the idea of a pollard in simplistic terms.

Due to the type of branch union which has originated from under the bark rather than from within the incremental growth of wood within the stem stem or branch, these pollard unions will be inherently weaker than a normal branch union. Given this, it is not wise to allow these branches to become too long or heavy otherwise the risk of failure increases to an unacceptable level.

Therefore, depending on the species of tree and the rate of responsive growth, pollarded trees usually need to be re-pollarded where they are cut back to the previous pollard points on a cyclical basis (often between 3 and 10 years). It is important not to take the easy option and cut below the pollard point as this will create a larger surface area for the tree to heal, causing unnecessary stress.

The most important things to consider when choosing pollarding as management option for your tree are whether a dense crown and cyclical management are right for you, your tree and the landscape and to remember that an unmanaged pollard can become a serious safety risk.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed